Mont Royal Montreal to Museum of Fine Arts Montreal

| Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal | |

| |

| Location of the Museum in Montreal | |

| Established | 23 April 1860 (1860-04-23) [ane] |

|---|---|

| Location | 1380, rue Sherbrooke Ouest Montreal, Quebec H3G 1J5 |

| Coordinates | 45°29′55″N 73°34′48″W / 45.4987°Due north 73.5801°Westward / 45.4987; -73.5801 Coordinates: 45°29′55″N 73°34′48″W / 45.4987°Due north 73.5801°Due west / 45.4987; -73.5801 |

| Type | Art museum |

| Visitors | 1.3 one thousand thousand (2017)[2] |

| Director | Stéphane Aquin |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA; French: Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, MBAM ) is an art museum in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It is the largest art museum in Canada by gallery infinite. The museum is located on the historic Gold Square Mile stretch of Sherbrooke Street.

The MMFA is spread across five pavilions, and occupies a total floor surface area of 53,095 square metres (571,510 sq ft), 13,000 (140,000 sq ft) of which are exhibition space. With the 2016 inauguration of the Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion for Peace, the museum campus was expected to go the eighteenth largest art museum in North America.[iii] The permanent collection included approximately 44,000 works in 2013.[3] The original "reading room" of the Art Clan of Montreal was the forerunner of the museum'due south current library, the oldest art library in Canada.[iv]

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts is a member of the International Grouping of Organizers of Large-scale Exhibitions,[5] likewise known as the Bizot Group, a forum which allows the leaders of the largest museums in the world to exchange works and exhibitions.

Founded in 1860, it is the oldest art museum in Canada.[6] In 2020, it was the most visited art museum in Canada.[7]

History [edit]

Beginnings [edit]

Exhibition room, Art Gallery, Montreal, 1879

Founded in April 1860 by Anglican bishop Francis Fulford, the Art Association of Montreal was created to "encourage the appreciation of fine arts amidst the people of the city".[8]

Since information technology did not have a permanent place to store acquisitions the Fine art Association was non able to learn works to display nor to seek works from collectors. During the following twenty years, the organization had an itinerant existence during which its shows and expositions were held in diverse Montreal venues.[9]

In 1877, the Art Association received an exceptional souvenir from Benaiah Gibb,[10] a Montreal businessman. He gave the cadre of his fine art drove consisting of 72 canvases and 4 bronzes. In addition he donated to the Montreal establishment a building site on the north-due east corner of Phillips Square and further the sum of coin of $8,000. This latter gift was on condition that a new museum be constructed on the site within three years.[11] On the 26 May 1879, the Governor General of Canada, Sir John Douglas Sutherland Campbell, inaugurated the Art Gallery of the Art Association of Montreal, the starting time building in the history of Canada to be synthetic specifically for the purpose of housing an art collection.[12] The Art Gallery at Phillips Square, designed by the Hopkins and Wily architecture house,[thirteen] comprised an exhibition room, some other smaller room (known every bit the Reading Room)[4] reserved for graphic works besides as a lecture hall and an embryonic art school. The museum was enlarged in 1893 by founding fellow member G. Drummond's nephew, Andrew Thomas Taylor, with decorative carving by sculptor Henry Beaumont.[14] The Art Association held an almanac show of works created by its members also as a Spring Salon devoted to the works of living Canadian Artists.

The gift fabricated by Benaiah Gibb was a watershed event in the founding of the museum'south collection. The generous gift engaged a keen interest in the public and, because of it, the donations multiplied.

Move to Sherbrooke Street West [edit]

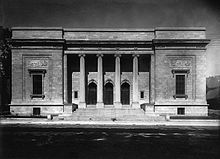

Besides cramped at its original location, the Art Association strongly considered the thought of moving from Phillips Square to the Golden Square Mile, where most of the city's fiscal aristocracy lived at the time. They settled on the site of the abandoned Holton Business firm, on Sherbrooke Street West, for the structure of the new museum. Senator Robert Mackay, the owner of the belongings, was convinced to sell the firm for a skillful price.[fifteen] A committee responsible for the construction of the museum was formed consisting of James Ross, Richard B. Angus, Vincent Meredith, Louis-Joseph Forget and David Morrice (the begetter of painter James Wilson Morrice).[fifteen] Most members of this commission offered a considerable amount of their own money for the construction of the museum. This included a big donation by businessman James Ross.[16] The Phillip's Square location was demolished in 1912, and is now a Burger Rex.

A limited architectural design competition was conducted to select an architect among three architectural firms that were invited to apply. The museum commission selected the project proposed by brothers Edward Maxwell and William Sutherland Maxwell. Trained in the Beaux-Arts tradition, they proposed a building that catered to French gustatory modality of the time: sober and majestic.[17] Work began in the summertime of 1910 and finished in the fall of 1912.

On Dec 9, 1912, the Governor Full general of Canada, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, inaugurated the new Museum of the Art Association of Montreal on Sherbrooke Street West in front of 3,000 people present for the occasion.

Modern era [edit]

In 1949, the Art Association of Montreal was renamed equally the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, which was more than representative of the institution'south mandate.[18]

In 1972, the MMFA became a semi-public institution funded mainly by government funds.[nineteen]

An expansion of the museum was undertaken during the 1970s culminating in 1976, with the opening of the Liliane and David M. Stewart Pavilion. Designed by architect Fred Lebensold the building backs directly onto the back of the Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion. The building'south architecture is modernist, made of concrete structures located along du Musée Avenue and in dissimilarity with the classical architecture of the first pavilion. It was controversial at the time, despite innovations like the ceiling box for a track lighting and large open interior. The pavilion houses nearly 900 decorative art and design objects. Most objects come from were donated by Liliane and David Chiliad. Stewart, hence the name of the pavilion. The collection includes furniture, glass, silverware, textiles, ceramics and works of industrial design. These objects were fabricated of a multifariousness materials, reflecting their origins in dissimilar countries and time periods.[20]

The engagement of Bernard Lamarre in 1982 equally president of the lath of directors, revitalized the museum after several difficult years.[21] In the mid 1980s, he proposed a major expansion of the museum. This proposal led to the structure of the Jean-Noël Desmarais Pavilion.[22] In 1991, the museum's third building, designed by Moshe Safdie, was built on the s side of Sherbrooke Street. It was funded past contributions from governments and the members of the business community, notably the Desmarais family. Safdie's architectural pattern incorporated the facade of New Sherbrooke Apartments, an apartment-hotel that occupied the site since 1905.[23]

1972 robbery [edit]

On September 4, 1972, the museum was the site of the largest art theft in Canadian history, when armed thieves made off with jewellery, figurines and xviii paintings worth a full of $ii million at the fourth dimension (approximately $12.5 meg today), including works by Delacroix, Gainsborough and a rare Rembrandt landscape (Landscape with Cottages). 1 painting, believed at the time to accept been a Jan Brueghel the Elderberry but afterwards reattributed to one of his students, was returned by the thieves as a mode of opening ransom negotiations; the rest take never been recovered. The thieves too have never been identified, although there is at least i informal doubtable.[24] In 2003, The World and Postal service estimated that the Rembrandt lonely would be worth $1 million.[25]

With the insurance money from the theft, the museum bought a large Peter Paul Rubens painting, The Leopards, which it promoted every bit the largest Rubens in Canada. Notwithstanding, years afterwards a conservator had the pigment tested and plant that the red pigments in it were mixed around 1687, iv decades after Rubens died; the painting has since been reattributed to Rubens' students. In 2007, on the 35th anniversary of the theft, it was removed from exhibit and remains in storage.[24]

2011 theft [edit]

1 day before the 39th ceremony of the 1972 theft, a visitor took a xx-by-21-centimetre (7.9 by 8.3 in) Roman marble caput from the 1st century CE from its pedestal. The perpetrator was able to escape the museum earlier the head's absence was discovered. Late in Oct 2011, about viii weeks after the original theft, a similarly-sized sandstone relief of a guard'due south head dating to 5th-century-BCE Persia was stolen the same way.[26] The two works were valued at $1.3 million together.[27]

In late 2013 a tip led investigators to the home of Simon Metke, an Edmonton man. The SQ, in conjunction with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, executed a search warrant and recovered the Farsi piece in January 2014. He was charged with possession of stolen property, possessing the proceeds of a crime and possessing a controlled substance for the purpose of trafficking; his girlfriend faced the latter two charges as well.[28]

Metke pled guilty to the first charge in April 2017. He and the prosecutors agreed that while he did not know the relief had been stolen, he could take taken more steps to define that it had not been than but doing a Google search on "Is a Mesopotamian artifact missing?" He received a provisional discharge with probation and community service as his sentence; a grapheme in the 2016 film Yoga Hosers was inspired by him later on the story was reported in the media.[29]

The insurance company had taken legal ownership of the relief every bit a effect of paying the claim, and while the museum could have bought it back by simply repaying the claim it declined to do and so, equally the relief was offered for sale at the 2016 Frieze Art Fair.[30] While police suggested at the time of Metke'southward arrest they had some leads on the thief, he has not been identified. The Roman head besides remains missing every bit of 2017.[28]

Pavilions [edit]

Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion

Claire and Marc Bourgie Pavilion, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, formerly the Erskine and American United Church building

Atrium of the Jean-Noël Desmarais Pavilion, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

The museum is partitioned into five pavilions: a 1912 Beaux Arts building designed by William Sutherland Maxwell and brother Edward Maxwell,[31] now named the Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion; the modernist Jean-Noël Desmarais Pavilion across the street, designed by Moshe Safdie, built in 1991; the Liliane and David M. Stewart Pavilion, the Claire and Marc Bourgie Pavilion built 2011 and recently inaugurated the Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion for Peace.

While the Desmarais Pavilion houses modern and gimmicky fine art collection, the Hornstein'southward focus is specifically archæology and ancient art; the Lilian and David M. Stewart is devoted to decorative arts and design. The Claire and Marc Bourgie houses the Quebec and Canadian art, and the new Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion for peace is the dwelling house for the international fine art collection.

On Feb 14, 2007, the museum's administration board announced its project to convert the Église Erskine and American, located on Sherbrooke West street, into a Canadian art pavilion. This new pavilion allowed the museum to double the display surface currently defended to Canadian artists. A Romanesque Revival church building with Tiffany stained drinking glass, dating from 1893–94, the church had been designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1998.[32] [33] It was named the Claire and Marc Bourgie pavilion, as a recognition of the family's considerable financial support, and opened in 2010.

With the addition of a 5th pavilion, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts occupies a surface area of 53,095 square metres (571,510 sq ft), of which thirteen,000 foursquare metres (140,000 sq ft) is defended to exhibition space. The expansion will make it the eighteenth largest art museum in Northward America.[three]

| Pavilion | Surface expanse |

|---|---|

| Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion (1912) | 5,546 thousand2 (59,700 sq ft) |

| Liliane and David G. Stewart Pavilion (1976) | 9,610 m2 (103,400 sq ft) |

| Jean-Noël Desmarais Pavilion (1991) | 22,419 m2 (241,320 sq ft) |

| Claire and Marc Bourgie Pavilion (2011) | 5,460 m2 (58,800 sq ft) |

| Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion for Peace (2017) | 4,363 g2 (46,960 sq ft) |

| Sculpture Garden | 2,033 mtwo (21,880 sq ft) |

| total: | 48,528 k2 (522,350 sq ft) |

Collection [edit]

In 1892, John W. Tempest ancestral lx oil paintings and watercolor paintings also as a trust fund for the purchase of works of fine art. This was the main source of income for the museum's conquering of European paintings until the 1950s.[34]

In the late 19th and early on 20th century, the large fine art collections owned by many prominent Montreal families became dispersed through shared inheritance. Yet, some heirs made large donations to the museum, such members of the Drummond, Angus, Van Horne, and Hosmer families, amid others.[34] In 1927, a collection of over 300 objects, including 150 paintings, was donated by the descendants of Businesswoman Strathcona and Mount Regal.[34]

In 1917, the Fine art Clan of Montreal created a department devoted to the decorative arts. The section was entrusted to Frederick Cleveland Morgan, who became the curator of the collection on a voluntary basis from 1917 until his death in 1962. Morgan added more than vii,000 pieces in the class of acquisitions, bequests or donations to the museum's collection.[35] He also expanded the mandate of the museum, from an institution dedicated solely to the fine arts to an encyclopedic museum, open to all forms of art.[36]

Since 1955, the museum gained the conquering funds it needed to buy Canadian or foreign works from the legacy of Horsley and Annie Townsend. Several gifts and bequests are made by the heirs or descendants of the collectors who founded the Art Association. Other donations come up from new donors such as Joseph Arthur Simard, who in 1959 offered a collection of 3,000 Japanese incense boxes that belonged to the French statesman Georges Clemenceau.[37]

In 1960, the centennial of the founding of the Art Clan of Montreal was highlighted past the publication of a catalog of selected works from the collection and a museum guide.

On September iv, 1972, a major theft took place at the museum. Fifty objects were taken including 18 paintings, including works by Peter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Eugène Delacroix that were never recovered.[37]

Major contributions take been made by Renata and Michal Hornstein since the 1970s. These accept included works by Old Masters, every bit well as several of the largest collections of drawings of the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler.[38]

These gifts expanded the range of the museum's collections, and reached a peak in 2000, with admission of the modern design collection assembled by Liliane M. Stewart and David Yard. Stewart, long a part of the Montreal Decorative Arts Museum and exhibited at the MMFA from 1997 to 2000.[38] [39] Liliane One thousand. Stewart donated over five,000 objects to the museum's drove (estimated value of C$fifteen million).

Affiliations [edit]

The museum is affiliated with the Canadian Museums Association, the Canadian Heritage Information Network, and the Virtual Museum of Canada.

Come across too [edit]

- List of art museums

- List of museums in Montreal

- Civilisation of Montreal

References [edit]

- ^ Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/evenements/ldt-512, Fondation de l'Art Clan of Montreal

- ^ Steuter-Martin, Marilla (January 16, 2018). "Montreal Museum of Fine Arts brings in record one.3 million visitors". CBC News. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c "2012-13 Annual Report" (PDF). Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

- ^ a b MMFA Library Archived January 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Bizot Policy Statement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ Montreal Museum of Fine Arts "The story of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts"

- ^ "Company Figures 2020: top 100 fine art museums revealed as omnipresence drops by 77% worldwide". The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. March 30, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ Georges-Hébert Germain, United nations musée dans la ville. Une histoire du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 2007, @p.15.

- ^ Georges-Hébert Germain, Un musée dans la ville. Une histoire du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 2007, @p.25.

- ^ fr:Benaiah Gibb

- ^ Georges-Hébert Germain, Un musée dans la ville. Une histoire du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 2007, @p.thirty.

- ^ Georges-Hébert Germain, Un musée dans la ville. Une histoire du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 2007, @p.26.

- ^ "Hopkins, John William." Hopkins, John William | Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada. Accessed March xiv, 2018. http://dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org/node/1525.

- ^ Wagg, Susan. 2014. Compages of Andrew Thomas Taylor: Montreal's Square Mile and Beyond. Montreal: MQUP. 144.

- ^ a b Germain, Georges-Hébert (2007). Un musée dans la ville. Une histoire du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal (in French). p. 54.

- ^ Michel Champagne. "Montreal Museum of Fine Arts". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Germain, Georges-Hébert (2007). Un musée dans la ville. Une histoire du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal (in French). p. 55.

- ^ Germain, Georges-Hébert (2007). Un musée dans la ville. Une histoire du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal (in French). p. 97.

- ^ see Mission and History tab Archived March 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pepall, Rosalind (2012). "Le design au fil des siècles : actuel, intemporel, surprenant". Revue K du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal (in French) (Bound): 12. ISSN 1715-4820.

- ^ Germain, Georges-Hébert (2007). Un musée dans la ville. Une histoire du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal (in French). p. 198.

- ^ "Bernard Lamarre GOQ". National Society of Quebec. Government of Quebec.

- ^ "Rue Sherbrooke Ouest (entre Atwater et Peel)". Base de donnés sur le patrimoine. Grand répertoire du patrimoine bâti de Montréal. Retrieved Jan 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Sezgin, Catherine Schofield (Fall 2010). "The Skylight Caper: The Unsolved 1972 Theft of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts" (PDF). The Journal of Fine art Law-breaking (4): 57–68. ISSN 1947-5934. Retrieved Baronial 27, 2017.

- ^ "CBC Digital Archives, Fine art heist at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts". Archives.cbc.ca. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Knelman, Joshua (February 14, 2012). "Two valuable artifacts stolen from Montreal museum". The Globe and Mail . Retrieved Baronial 17, 2017.

- ^ Montgomery, Sue (February 14, 2014). "Police track down artifact stolen from Museum of Fine Arts". Montreal Gazette . Retrieved August 17, 2017 – via PressReader.

- ^ a b "Stolen artifact from Montreal museum recovered in Edmonton". CBC News. Feb 14, 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Pruden, Jana (April 28, 2017). "The Edmonton homo who inspired 'Yoga Hoser' arrested for possession of a $1.2-1000000 ancient statue". The Globe and Mail . Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Charles Saumarez; Philips, Sam (October 6, 2016). "What to run into at Frieze 2016". Royal Academy of Fine art. Retrieved Baronial 19, 2017.

- ^ "5 Best". Montreal Gazette. December 7, 1985. p. 22. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ "Erskine and American United Church". Directory of Designations of National Historic Significance of Canada. Parks Canada. Retrieved July 30, 2011. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ Erskine and American United Church. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved July xxx, 2011.

- ^ a b c Guide des collections du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 2003, p. 19.

- ^ Guide des collections du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 2003, p. 21.

- ^ Bondil, Nathalie (2012). "Le design moderne selon Liliane M. Stewart : une collection d'exception, une entreprise de 50'camaraderie". Revue Grand (in French). Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Spring 2012): 14. ISSN 1715-4820.

- ^ a b "Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal - De fifty'Fine art Clan of Montreal au musée des beaux-arts de Montréal" (in French). Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012.

- ^ a b Guide des collections du musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 2003, p. 22.

- ^ "Collection - Decorative Arts and Design". Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved Jan 28, 2014.

External links [edit]

- Official website

- Inauguration of the Ben Weider Napoleonic Galleries at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

- Georges-Hébert Germain, Un musée dans la ville

0 Response to "Mont Royal Montreal to Museum of Fine Arts Montreal"

Post a Comment